We usually view the placebo effect as a treatment of faith. If you believe the pill will help you, it will; the only condition is that you must believe it. In this light, it is plausible to dismiss the notion of placebo having an effect on animals. Especially pets in veterinary medicine.

After all, cats and dogs can’t possibly know how good the homeopathic remedy or spiritual healing is; thus, if they work on dogs or cats, it can’t be placebo. But can it? Does placebo work on animals?

In this article, you will learn how placebo works on animals. What else is hiding behind placebo’s therapeutic effects, and can we use the magic power of placebo to treat our pets—dogs, cats, and others.

Do animals respond to placebo?

Straightforward answer first—yes, placebo DOES affect animals.

That’s right. It indeed seems that consciousness is important for the placebo effect to manifest itself. At the same time, this conscious thought is not all that there is to it.

Placebo is much more, and at the same time, much less than the average person understands of it. How can this be? We’ll dive into that later. But first…

There is a significant amount of evidence that the placebo effect is present in veterinary medicine. Regardless of question how and why.

Placebo responses have been observed in various animals: rats, dogs, monkeys, horses, and others. It is recognized well enough that placebo control is included in trials of new veterinary drugs. And for one simple reason—animals do respond to placebo.

But how does this happen? If an unsuspecting dog receives placebo, how can he possibly expect to (and actually) get better from it? The first reason is because placebo is not only in the mind. It also works inside the body. Second, saying that a pets don’t have brainpower to understand that he is being treated is an underestimation of pets’ cognitive abilities (at least in few cases).

How does placebo work?

Here are a few suggested theories regarding how placebo in human medicine is explained. You will see that these ideas are all totally valid for pets, as well:

- Classical conditioning. A remarkable demonstration of a placebo-like effect in pets was shown by Dr. Krylov in the early 20th century. A dog was regularly injected with morphine (testing of animals was viewed radically differently back then). After just few days, the dog showed negative side effects of morphine injection (vomiting, dizziness, etc.) whenever the animal arrived in the procedure room. Even without receiving the injection. In this case, not the mind but rather the immune system of the dog learned to react accordingly. In a similar way, the body can learn to react to medication in many different ways. For example, the first injection puppies and kittens normally get is their first vaccine, followed by a booster a few months later. It’s not only about the injection; every detail, contribute to the pet’s body “learning” that the immune system needs to be activated. The scent of the veterinary clinic, sound of a medicine bottle opening, and even an owner getting nervous before a visit. Beyond this example, there are many ways that a pet’s or person’s body, can “learn” that getting an injection, taking a pill, or getting a surgery means it’s time to start self-repair. Besides, it happens without the person being conscious of it

- Expectation of getting better. If you know that you will get better, you will get better; that is how most people understand placebo, and it applies to animals too. For example, if a dog gets a pain killer injection, it usually kicks in rapidly. Nothing can stop him from connecting the two events. That is one thing. Pet owner’s expectations about the treatment can influence the outcome, too. On one hand, this is because optimistic owners may follow a veterinarian’s instructions more precisely. On the other hand, an owner’s stress can be translated to pets, and there is no reason to think that the opposite (optimism, or the lack of stress) wouldn’t transfer in kind.

Human contact. While it’s under debate that the positive attitude of medical staff in human healthcare could have significant influence on recovery. Different health benefits from human contact (such as lowered heart rate or blood pressure) are present in animals. It has been observed from dogs and horses to monkeys and rats. On the surface, it seems plausible that petting and gentle handling is able to reduce the stress of an animal. Even more surprising, similar effects are present in cases when the encounter with humans isn’t at all pleasant. For example, receiving an injection in a veterinary clinic. A vet visit is rarely a positive experience for pets.

Human contact. While it’s under debate that the positive attitude of medical staff in human healthcare could have significant influence on recovery. Different health benefits from human contact (such as lowered heart rate or blood pressure) are present in animals. It has been observed from dogs and horses to monkeys and rats. On the surface, it seems plausible that petting and gentle handling is able to reduce the stress of an animal. Even more surprising, similar effects are present in cases when the encounter with humans isn’t at all pleasant. For example, receiving an injection in a veterinary clinic. A vet visit is rarely a positive experience for pets.

It is clear that most of above suggested mechanisms of how a placebo might work them stand on plausible ground. Also, they are not mutually exclusive. While classical conditioning contributes most, others appear important for the placebo effect in both human and veterinary medicine. But that is only a part of the story.

Is placebo always a placebo?

Placebo isn’t always what you think it is. We have already explained why it is more than most of you thought before; at the same time, placebo is also less than what the majority thinks it is.

In general, if a patient gets better when using drugs with no active ingredient (or without a helpful active ingredient), it is recognized as a placebo. But it doesn’t have to be.

Here are few examples of when placebo isn’t really placebo:

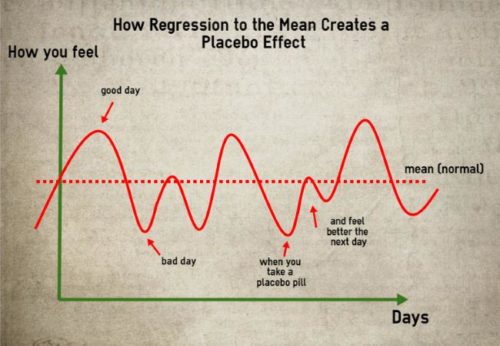

- Regression to the mean. Patients with chronic problems tend to get better and worse all the time. There are good days, bad days, and normal days comprising the majority of days. We more commonly take medicine on bad days. That means the next day, on average, is more likely to be a better one, regardless of the treatment. It would have come anyway, but a patient will experience “an improvement” after taking a pill.

- Biased conclusions. We and our clever human brains are very good at misconstruing our conclusions about almost anything. We tend to remember good things more vividly and shrug off bad ones as irrelevant. That means, for example, if a pet owner treats his dog’s arthritis with homeopathy, he can come to wrong conclusions. He is likely to remember every time in which his dog got better after the treatment. At the same time, he may write off as irrelevant all those times when improvement did not follow. Even if the treatment helps only half of the times, he will conclude that it works. If you think only pet owners do this, think again. Academics are also guilty of distorting reports (both consciously or unconsciously) on drug trials and other research pieces.

- Natural resolution. Not all medical conditions require active treatment. Some just need to rest or remove the root cause. There is a joke: if you treat the common cold, it will go away in a week, but if you do not, you will be well again after seven days. That is why the common cold is very adaptive to placebo treatments—it tends to resolve by itself. There are numerous problems that the body can get hold of all alone, not always it is placebo.

- Non-specific effects of the treatment. In certain cases, it may happen that the treatment of choice indeed does help the patient to recover, but not in a way that is expected. The most banal example is if you treat dehydration with magnesium pills. Magnesium does not affect hydration, but the water you drink while taking the pills does.

All in all, we are not here on a mission to destroy placebo or alternative medicine. We want to demonstrate that placebo and placebo-like effects, go beyond human mind. They do not require a patient to consciously know that the treatment will help.

Is the placebo effect an unresearched magic cure?

Finally, there is still one thing that cannot be left unattended. Can placebo provide a whole new area in which doctors could work? Can we treat humans—and can we treat our pets—using the magic powers of placebo?

It sounds extremely tempting. What about an easy to administer, cheap medicine that delivers the cure just as well as conventional drugs? Cancer treatment without chemotherapy? Effective pain killers without damage to internal organs?

Sounds good, but if it really is possible, we aren’t there yet. As it is now, placebo is unlikely to cure a disease completely on its own. Will it ever? Besides, “just as well as convention drugs” seems sarcastic. Trials, by default, recognize drugs only when they perform significantly better than placebo.

Some studies show that placebo is as “good” as not treating at all. Others suggest that placebo is getting stronger over time. The latter might be because people nowadays expect more from treatments. Better expectation should equal stronger placebo response. But it also could be because the clinical trials have attained higher quality over time. A low-quality trial is likely to exaggerate the effect of the investigated drug and belittle the effect of placebo.

Placebo is not at all powerful when left on its own

The sad truth is that when we strip the placebo effect from all the other things it is surrounded by there isn’t much left. That, however, does not mean that the we shouldn’t explore and maximize placebo effect when possible.

Veterinarians could benefit their patients if the understand how placebo (and all the things that look like placebo) work. For example, if we know that a dog’s body can learn to react to morphine, it is easy to wonder what else can it learn to react to.

At the same time, relying solely on placebo is simply unethical if there is an effective medicine available. If there isn’t, that might turn out to be a different story.